What is Vanitas?

Vanitas is a genre of Still life Painting characterized by the presence of symbolic objects that allude to the ephemerality of life and to death. It was particularly popular in the 16th and 17th centuries in the Netherlands. The term vanitas derives from the Latin expression “vanitas vanitatum” (“vanity of vanities”) a verse taken from the Bible, precisely from Ecclesiastes 1:2; 12:8.

It derived from the adjective “vanus” – literally “empty”, “transient”, “futile”, “worthless” in Latin. In the biblical verse, the concept of vanitas translated the Hebrew word hevel, which also alluded to the idea of transitoriness of life. Vanitas, in fact, indicates the precariousness of human condition and the inevitable perishment of earthly pleasures.

It is an iconography which at the very beginning, as its biblical etymology confirms, had a moralizing and religious purpose. It invites to abandon worldly, trivial, goods and ephemeral luxuries, to focus on the redemption and soul salvation.

Notable Vanitas Artworks

Self-Portrait with Vanitas Symbols, David Bailly, 1651

Vanitas-Still Life, Pieter Claesz, 1628

Emblem of Death, Pieter Van Steenwijck, 1635-1640

Vanitas Still Life, Jacques de Gheyn II, 1603

Still Life with Skull (Nature morte au crâne), Paul Cézanne, 1890-1893

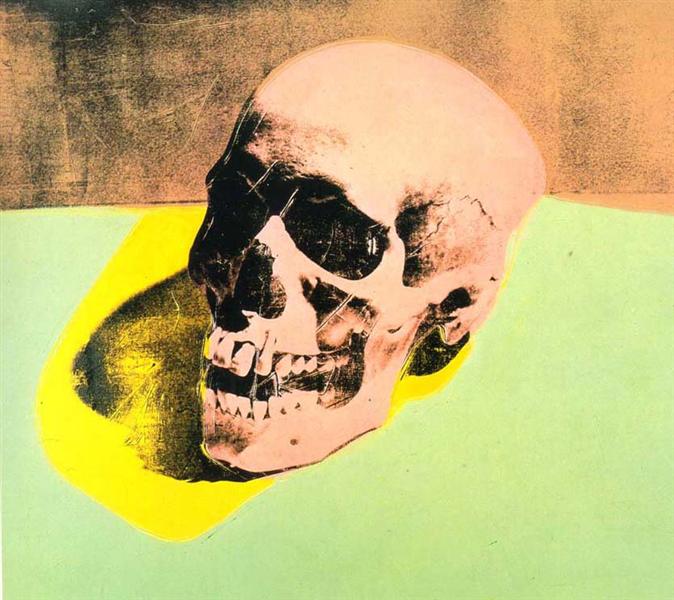

Skulls, Andy Warhol, 1976

History of Vanitas

The genre of Vanitas in Still Life Painting includes a specific iconography and a particular attention for certain symbolic subjects. Vanitas paintings are characterized by elements which are linked to the theme of ephemeral life and inexorable death: skulls, hourglasses, consumed candles, soap bubbles, decayed fruits and perishing flowers are the most popular. Furthermore, vanitas pictures also include symbols of wealth like jewelry or golden coins; symbols of arts and sciences, like books and musical instruments, and symbols of earthly goods and venal activities, like playing cards, wine glasses or pipes. Explicit warnings written in cartouches such as “Vanitas vanitatum”, “Memento mori”, etc., are equally frequent in Vanitas Still Lives. Each element is allegorically related to the concept of the transience of life, beauty, and time; it invites viewers to consider the mortal nature of their condition.

The origin of the concept of vanitas can be found in the Middle Age, a period characterized by the contempt for the body and the materiality, and by a moralistic and spiritual exaltation. Medieval funerary art is the most explicit medium which embodies the idea of macabre and death in art. However, other examples of vanitas in the artistic domain are traceable in the late Renaissance, where pictures of skulls and other symbols of death were frequently painted on the reverse sides of portraits, as memento mori (reminders of mortality).

Vanitas painting had its greatest diffusion in the 16th and especially in the 17th century, particularly in the Netherlands during Dutch Golden Age and in the town of Leiden. It is in that period, between the 1550 and the 1620, with a decline around 1650, that vanitas reached an autonomous genre status, which freed it from its merely decorative function. Leiden, being an important centre for Calvinist religion, offered a fertile ground for a genre like vanitas that exhorted adherence to moral codes and Christian values.

However, vanitas also became an expedient for painters to virtuously represent objects that otherwise would not be accepted in painting. Vanitas Still Lives were in fact characterized by meticulous research in the chiaroscuro and in the representation of light, shadows and proportions.

Still Life painters of Dutch Golden Age, such as David Bailly, Jan Davidsz de Heem, Willem Claesz Heda, Pieter Potter, and Harmen and Pieter van Steenwyck, were also interested in the iconography of vanitas, and they influenced subsequent masters like Rembrandt, too.

Vanitas has in art history a moral function, which reminds humans of the volatility of their pleasures and the transience of their actions and life achievements. However, the allegorical symbols of this artistic genre can also be interpreted as an exhortation to enjoy life in its brevity, a reminder to seize the day.

Notable Vanitas Artists

- David Bailly, 1584–1657, Dutch

- Jan Davidsz De Heem, 1606 – 1683/1684, Dutch

- Willem Claesz Heda, December 14, 1593/1594 – 1680/1682, Dutch

- Pieter Potter, 1597 – 1652, Dutch

- Harmen Van Steenwijck, 1612 – 1656, Dutch

- Pieter Van Steenwijck, 1615 – 1666, Dutch

- Pieter Claesz, 1597–1 January 1660, Dutch

- Jacques de Gheyn II, 1565 – 29 March 1629, Dutch

- Hans Holbein the Younger, 1497 – between 7 October and 29 November 1543, German

- Guercino, February 8, 1591 – December 22, 1666, Italian

- Salvator Rosa, July 22, 1615 – March 15, 1673, Italian

- Antonio de Pereda y Salgado, 1611 – 1678, Spanish

Related Terms

- Still Life

- Oil Painting

- Chiaroscuro

- Genre Painting

- Dutch Golden Age

- Flemish Art

- Renaissance

- Baroque

- Allegory

- Memento Mori